Touching is the ultimate goal of the artifices of Ernesto Rancaño, as well as seducing with the tenderness of an apprehensive gesture. It is the empirical and visual code of abandonment and loneliness, the inexact nomenclature of all those feverish feelings that man devours in silence, on the sly, fearful of exposing the signs of his lassitude, the idiolect clung to his wanderings. The most unreservedly human is the universe that motivates him. Therefore, he is a poet overwhelmed of nostalgia, risky and pleased in the vacuum of anguish. His sensitivity has a high tessitura, his hands, a supreme commitment, since they are abandoned to the task of translating into forms what the soul suffers.

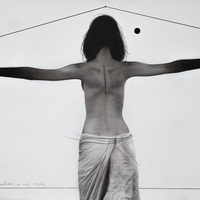

The rhetorical figure of pain is widely used in such endeavors. The image of medieval Christianity, deeply religious, as ecstatic as poignant, feeds it as narrative catalyst. Thus, the suffering of the soul is alluded in Rancaño’s oeuvre with the promptness of horrific physical lacerations, of sores and stigmas, ties and ballasts. Yet each of those scourges brings clung to it the seal of an absolute decorum that tends to compassion.

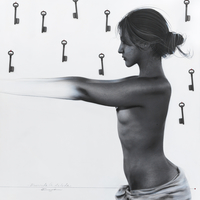

We will also find him striving in the supreme and the delicate things. On these lands he is excessively lyrical. Without any doubt, he is a master of allegory and the poetic image. He runs through the ways of the insubstantiality from the iciest to the most ardent extremes, among thorns and metallic flapping, shadows and lights; memories and anxieties summon him. The time will come when a warm torrent will flood him and hasty, he will embrace it just as he has done whenever it is about soul.